We use cookies

Using our site means you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies. Read about our policy and how to disable them here

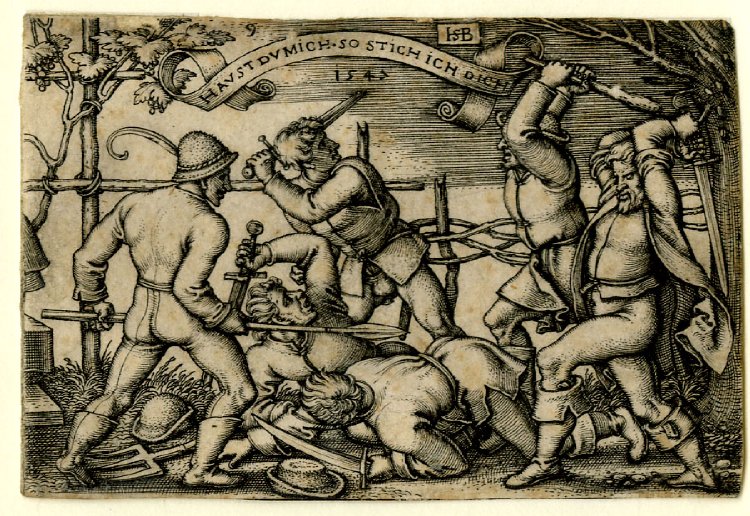

"HAVST DV MICH SO STICH ICH DICH" or "You cut me so I'll stab you". A peasant brawl is a charming topic for an engraving by Sebald Beham. It's at the British Museum but not on display, the spoilsports.[/caption]

Just as is the case today, martial artists addressing self-defence in medieval or renaissance Germany had to bear in mind the frameworks, legal and social, that governed the use of force. Even when violence was thus in some way condoned by such frameworks, it was not unconditionally endorsed but coded into a spectrum of force which needed to be justified by the opponent’s conduct.

For disciples of the Liechtenauer tradition, The Martial Ethic… is especially interesting as it addresses transitions in military technology and the nature of the “armed civilian” burgher in the early sixteenth century. This is reflected in the transition to longsword play for the Fechtschule seen in, for example, Meyer. HEMA’s sources from this time and place also often reflect the spectrum of violence mentioned above - an unarmed fight, a fight with the flat of the sword or the edge, and a stabbing would all be viewed differently.

Personally the most significant takeaway was how empty the term “civilian” was - with the requirements for arms and the proficiency to use them closely tied to the concept of citizenship itself, the classic feudal division of “those who work“ and “those who fight” seems inapplicable. So much for the Ritterlicher kunst!

If you don’t study German arts, try not to be put off by the title - there’s useful comparisons against other countries in here as well, although there are of course more specialised works out there on Italian renaissance duelling etc.

The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England by Ian Mortimer

"HAVST DV MICH SO STICH ICH DICH" or "You cut me so I'll stab you". A peasant brawl is a charming topic for an engraving by Sebald Beham. It's at the British Museum but not on display, the spoilsports.[/caption]

Just as is the case today, martial artists addressing self-defence in medieval or renaissance Germany had to bear in mind the frameworks, legal and social, that governed the use of force. Even when violence was thus in some way condoned by such frameworks, it was not unconditionally endorsed but coded into a spectrum of force which needed to be justified by the opponent’s conduct.

For disciples of the Liechtenauer tradition, The Martial Ethic… is especially interesting as it addresses transitions in military technology and the nature of the “armed civilian” burgher in the early sixteenth century. This is reflected in the transition to longsword play for the Fechtschule seen in, for example, Meyer. HEMA’s sources from this time and place also often reflect the spectrum of violence mentioned above - an unarmed fight, a fight with the flat of the sword or the edge, and a stabbing would all be viewed differently.

Personally the most significant takeaway was how empty the term “civilian” was - with the requirements for arms and the proficiency to use them closely tied to the concept of citizenship itself, the classic feudal division of “those who work“ and “those who fight” seems inapplicable. So much for the Ritterlicher kunst!

If you don’t study German arts, try not to be put off by the title - there’s useful comparisons against other countries in here as well, although there are of course more specialised works out there on Italian renaissance duelling etc.

The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England by Ian Mortimer For those who want to start their background reading at a lighter and less academic level than the previous book, this is a good general introduction to the Middle Ages, with a focus on daily living.

HEMA isn’t reenactment; it’s not directly relevant to know what weave our clothes might have been made of, or what lunch you might have eaten before getting into a sword fight. Yet consider - how affordable was a sword? How common was military service - and if so, locally or with travel? How common was long distance travel? How likely were you to get into a swordfight at home or when travelling? What, in full, was the lifestyle, the expectations and social network of the sword wielding historical figure we seek to emulate?

Mortimer’s work is pop history, undeniably and (in the hazy attribution and sourcing) unashamedly. It’d still be a great thing if more HEMA discussion was based on the view of medieval life that it offered and less on Monty Python and Blackadders’s presentations.

Motivational:

The Inner Game of Tennis: The Classic Guide to the Mental Side of Peak Performance by W Timothy Gallwey

For those who want to start their background reading at a lighter and less academic level than the previous book, this is a good general introduction to the Middle Ages, with a focus on daily living.

HEMA isn’t reenactment; it’s not directly relevant to know what weave our clothes might have been made of, or what lunch you might have eaten before getting into a sword fight. Yet consider - how affordable was a sword? How common was military service - and if so, locally or with travel? How common was long distance travel? How likely were you to get into a swordfight at home or when travelling? What, in full, was the lifestyle, the expectations and social network of the sword wielding historical figure we seek to emulate?

Mortimer’s work is pop history, undeniably and (in the hazy attribution and sourcing) unashamedly. It’d still be a great thing if more HEMA discussion was based on the view of medieval life that it offered and less on Monty Python and Blackadders’s presentations.

Motivational:

The Inner Game of Tennis: The Classic Guide to the Mental Side of Peak Performance by W Timothy Gallwey

I think there will be a whole column coming based on this classic book on sports psychology. The foundational concept of the book is that there’s two halves to playing tennis - an inner game and an outer game. In some ways, tennis applies well as to HEMA fencing. Both are open games played against a single opponent with very physical demands. If you didn’t know what an open game means in this context, it’s one in which the opponent’s actions influence yours directly. You can hit a perfect round of golf or sprint the 100m or play darts regardless of what your opponents do. Your actions in fencing and tennis alike, however, are dictated by the opponent’s.

Outer and inner, by Gallwey’s terms, are respectively the physical game that’s going on and your mental state. This book is about how to play the inner game better - for better tennis scores but also personal harmony. Yes, you should be forewarned the term “Zen” may appear in this book. For Gallwey analyses this Inner Game as a relationship between two component’s of your own mind - a doing and a telling, or an unconscious and a conscious. To quote:

I think there will be a whole column coming based on this classic book on sports psychology. The foundational concept of the book is that there’s two halves to playing tennis - an inner game and an outer game. In some ways, tennis applies well as to HEMA fencing. Both are open games played against a single opponent with very physical demands. If you didn’t know what an open game means in this context, it’s one in which the opponent’s actions influence yours directly. You can hit a perfect round of golf or sprint the 100m or play darts regardless of what your opponents do. Your actions in fencing and tennis alike, however, are dictated by the opponent’s.

Outer and inner, by Gallwey’s terms, are respectively the physical game that’s going on and your mental state. This book is about how to play the inner game better - for better tennis scores but also personal harmony. Yes, you should be forewarned the term “Zen” may appear in this book. For Gallwey analyses this Inner Game as a relationship between two component’s of your own mind - a doing and a telling, or an unconscious and a conscious. To quote:

within each player the kind of relationship that exists between Self 1 and Self 2 is the prime factor in determining one's ability to translate his knowledge of technique into effective action. In other words, the key to better tennis-or better anything-lies in improving the relationship between the conscious teller, Self 1, and the unconscious, automatic doer, Self 2.From this premise, Gallwey explores strategies for not just competitive performance, but for coaching, training and more. Without spoiling or summarizing the whole book, there’s an emphasis on being non-judgemental, and learning to observe without criticizing. After all, few errors are due to not desiring the objective, and most aren’t due to not understanding the actions needed. More common causes are over-tension caused by pressuring oneself or simple lack of repetition to bring unconscious competence. For me, one golden nugget hidden in this book was the section about Games People Play - in other words, ulterior battles that the game of tennis is merely a vehicle for. As well as winning, there are many others examined, from technical perfection to a social life, each with their own ambition and motivation. If you can’t admit to yourself which additional games you’re really playing, you’ll struggle to enjoy (or excel) in the literal obvious game you’re playing. I’ll stop there, since I’ve got another blog on that concept for HEMA planned. The Art of Learning: A Journey in the Pursuit of Excellence by Josh Waitzkin

If you don't get it, ask that friend with the cauliflower ear and taped up fingers.[/caption]

Anyway, the whole legit BJJ thing convinced me to read this, but it’s not mentioned anywhere in the book, which more or less concludes with the 2004 Tai Chi medal. It undoubtedly helps, just like The Inner Game of Tennis, that chess, push hands and BJJ are all open games.

So why read it, other than “Smallridge Says So”? You’re probably learning HEMA if you’re reading this. Learn how to learn it better.

This isn’t the most focused or practically applicable how-to book, but I said at the start of Part 1 of this article that these were reviews of personal favourites. I enjoyed the autobiographical nature, as some lessons were hard won. He addresses not just learning strategies but, at least as importantly, motivation and focus.

The best way to never become the brilliant HEMA fencer you know you can be is to give up completely. The second best is to settle for being an OK fencer. Motivation to stay training can be hard, especially at times when you don’t feel that you’re making progress or you’re burned out on the hobby, and you’ll find a lot on how to avoid either situation here. More accurately, you’ll find inspiration in Waitzkin’s account of how he struggled.

If you don't get it, ask that friend with the cauliflower ear and taped up fingers.[/caption]

Anyway, the whole legit BJJ thing convinced me to read this, but it’s not mentioned anywhere in the book, which more or less concludes with the 2004 Tai Chi medal. It undoubtedly helps, just like The Inner Game of Tennis, that chess, push hands and BJJ are all open games.

So why read it, other than “Smallridge Says So”? You’re probably learning HEMA if you’re reading this. Learn how to learn it better.

This isn’t the most focused or practically applicable how-to book, but I said at the start of Part 1 of this article that these were reviews of personal favourites. I enjoyed the autobiographical nature, as some lessons were hard won. He addresses not just learning strategies but, at least as importantly, motivation and focus.

The best way to never become the brilliant HEMA fencer you know you can be is to give up completely. The second best is to settle for being an OK fencer. Motivation to stay training can be hard, especially at times when you don’t feel that you’re making progress or you’re burned out on the hobby, and you’ll find a lot on how to avoid either situation here. More accurately, you’ll find inspiration in Waitzkin’s account of how he struggled.