After the history of foil fencing (here you go for part 1 and part 2) and the development of epee it is now time for the third part of our series by expert Malcolm Fare. If you've always wondered how sabre fencing was born and who it was most popular with in the beginning (no, it was not the military!), read on.

The Development of Sabre

by Malcolm Fare

Sabre fencing derives from the heavy military sword and naval cutlass, wooden or blunted versions of which were used for centuries in preparation for warfare. The first purpose-made practice sabre was the 16th century German

düsak, a heavy curved sword, usually made of wood but sometimes of steel, with a hole in the grip for the hand (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: A düsak replica

Fig. 1: A düsak replica

More popular in Britain was the cudgel or singlestick, which developed into a rural sport during the 17th century. Young farm workers would gather at country fairs and take part in bouts using an ash stick held in a wicker basket (Fig. 2). The winner was the first man to deliver a blow that drew an inch of blood.

Fig. 2: Example of a cudgel or singlestick

Fig. 2: Example of a cudgel or singlestick

Singlestick fighting was also taken up by the armed services as a preparation for swordplay. In his book

Broad-Sword and Single-Stick, 1890, C Phillipps-Wolley wrote, “There is just enough sting in the ash-plant’s kiss, when it catches you on the softer parts of your thigh, your funny bone or your wrist, to keep you wide awake and remind you of the good old rule of grin-and-bear-it.”

In 1856 the British army introduced the first purpose-made cavalry practice sword and 8 years later its gymnasium equivalent. With various modifications, these weapons continued to be made until 1911, when the last gymnasium sword was introduced (Fig. 3). The early years of the Royal Tournament, which developed into the biggest military tattoo in the world, included sabre v bayonet (1886) and sabre v sabre (1891).

Fig. 3: The so-called gymnasium sword

Fig. 3: The so-called gymnasium sword

At the same time, modern sabre fencing was being developed in Hungary and Italy, where the sabre was a popular duelling weapon. In 1851 the Hungarian fencing master Joseph Keresztessy opened a school that taught a new style of fencing using circular wrist motions as the basis for cuts and parries. Then, in the 1870s, the Italian fencing master Giuseppe Radaelli developed a light sporting sabre, with a thin triangular blade and a simple elliptical ring surrounding a narrow knuckle guard (Fig. 4). It had a slightly curved blade 820-880 mm long tapering from 12 mm wide at the guard to 8 mm at the tip and weighed just 450 g. A rival school evolved in southern Italy under Masaniello Parise and soon Italian fencing masters were demonstrating the new system all over Europe. Luigi Barbasetti introduced it to Austria, Italo Santelli to Hungary and Giuseppe Magrini to Britain.

Fig. 4: An early sabre guard

Fig. 4: An early sabre guard

Looked on with derision by army fencers, the sporting sabre was first demonstrated in England in 1893, when the inspector of gymnasia at Aldershot, Col. Fox, brought over the celebrated master Ferdinando Masiello of Florence with his pupil Giuseppe Magrini, who was to settle in this country and teach sabre in the army until his death in 1912. In his book

Cut and Thrust, 1927, Leon Bertrand vividly described an encounter between Magrini and a traditional army fencer:

“Magrini was a resplendent figure in black satin knee-breeches and silk stockings, waving a light and fragile-looking silver-plated sabre. In contrast Mr X was lifted on to the platform at the other end, clad in heavy canvas, shin guards and cage-like mask, clutching a heavy blunted cavalry sword. With gossamer touch, Magrini drew his blade swiftly across the chest to draw ‘first blood’. Mr X, who had made one wild attempt to follow the steel, abandoned defence and cut wildly at head. The flat of the blade curled over Magrini’s mask and he received the full force of the blow on his back. Believing his first impression of British sabre-play too bad - and too painful - to be true, Magrini advanced to the attack once more. Following a couple of bewildering feints came the circular cut with feathery touch. Once again Mr X floundered, hit out blindly, and for the second time his blade curled down the Italian’s spine, whereupon Magrini whipped off his mask, held out his hand and, despite his obvious agony, said distinctly, Thank you, sir. You are a very much better man than I.”

In April 1896 competitive fencing was given a great stimulus by being included in the first modern Olympic Games, where the new lightweight sabre was used. Two months later, separate open international three-weapon tournaments for professionals and amateurs were held for the first time in Paris. The winner of each event received 1000 francs and every participant received a bronze medal commemorating the tournament.

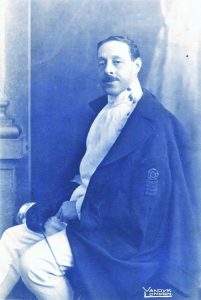

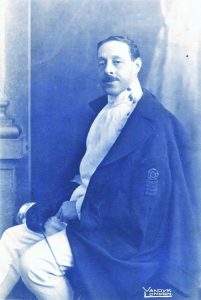

The first British sabre championship was held in 1898 and was won by the Irish all-round sportsman Captain Walter Edgeworth-Johnstone (Fig. 5), who won it again in 1900, having already been British heavyweight boxing champion in 1895 and 1896. He went on to become Chief Commissioner of the Dublin Metropolitan Police and was knighted in 1924.

Fig. 5: Captain Walter Edgeworth-Johnstone

Fig. 5: Captain Walter Edgeworth-Johnstone

The sabre champion was not required to fence in the following year’s championship until the final poule. Only in 1910 did the champion have to fence through the competition like everyone else.

At the 1908 Olympic Games in London specifications for sabre were: blade length not more than 880 mm (extended to 900 mm for the 1912 Olympics), guard 150 mm wide x 140 mm deep and maximum overall weight 500 g. These dimensions were later to be adopted by the FIE. But sabre was still regarded as essentially a military weapon and, in preparation for combat, the whole body was the target. It was only after the First World War finally proved the superiority of bullet over sword that the modern sabre target was adopted.

Sabre in the 1920s was dominated by servicemen not noted for their delicate play. A newspaper report of one championship noted that “when those game fighters Rear-Admiral the Hon. Leveson-Gower and Colonel Ronnie Campbell meet Captain Haycraft and Major Twist, all will bear the weals of battle, for blows will be hard and stinging... Artistry is not theirs, for their cuts to chest are more akin to carpet beating than to the light quick-drawn stroke of the Italian.”

Fig. 5: British sabre champion Edgar Seligman

Fig. 5: British sabre champion Edgar Seligman

The age of British sabre champions during the 1920s – all but one were over 30 – bore witness to the toll taken on young men by the war. Capt. Bill Hammond (1921) was 49, Archie Corble (1922 & 27) was 39 and 44, Edgar Seligman (1923 & 24) was 55 and 56, Capt. Guy Harry (1928) was a relatively young 31 and Col. Ronnie Campbell (1929) was 50. Fig. 6 shows Edgar Seligman (right) practising with Prof. Leon Bertrand.

Fig. 7: Lieut. Cecil Kershaw RN

Fig. 7: Lieut. Cecil Kershaw RN

The exception was three-times champion Lieut. Cecil Kershaw RN (Fig. 7), who was 25 when he won his first championship in 1920, and in 1924 became Royal Tournament dismounted champion-at-arms at all three weapons, receiving handsome decorative weapons made by Wilkinson (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8: Wilkinson decorated weapons

Fig. 8: Wilkinson decorated weapons

Pre- and post-WW2, the dominant sabreur was Dr Roger Tredgold (Fig. 9), British champion a record six times between 1937 and 1955, who would undoubtedly have won more titles had the war not intervened.

Fig. 9: Dr Roger Tredgold

Fig. 9: Dr Roger Tredgold

Sabre fencing continued to require the services of four judges and a referee well after the other two weapons became electrified, but eventually in 1986 a reliable system of recording hits electrically was perfected. The sudden contact of blade against

metallic jacket,

mask or bib triggers an electric circuit by way of a

socket inside the

guard connected to a

bodywire and then to a reel and ground lead to activate a

scoring machine.

The first British sabre championship for women took place in 1989, with Sue Benney winning six of the first eight events. But her record was eclipsed by Louise Bond-Williams (Fig. 10), who became Britain’s youngest senior champion in 1997 at the age of 14 years, 10 months, and went on to win a record 10 titles.

Fig. 10: Louise Bond-Williams

Fig. 10: Louise Bond-Williams

Women’s sabre finally became recognised by the FIE in 1998 with a trial event at the world championships and the following year official individual and team events were held, but full parity at the Olympic Games was not achieved until 2008. Even then, fencing was restricted to a total of ten sets of medals, so that one individual and one team event had to be dropped by rotation from each Games. Only after years of lobbying by the FIE, has the IOC accepted that the Olympics should recognise all 12 fencing disciplines with medals, something that will happen for the first time in 2020.

Malcolm Fare

Fig. 1: A düsak replica

Fig. 1: A düsak replica  Fig. 2: Example of a cudgel or singlestick

Fig. 2: Example of a cudgel or singlestick  Fig. 3: The so-called gymnasium sword

Fig. 3: The so-called gymnasium sword  Fig. 4: An early sabre guard

Fig. 4: An early sabre guard  Fig. 5: Captain Walter Edgeworth-Johnstone

Fig. 5: Captain Walter Edgeworth-Johnstone  Fig. 5: British sabre champion Edgar Seligman

Fig. 5: British sabre champion Edgar Seligman  Fig. 7: Lieut. Cecil Kershaw RN

Fig. 7: Lieut. Cecil Kershaw RN  Fig. 8: Wilkinson decorated weapons

Fig. 8: Wilkinson decorated weapons  Fig. 9: Dr Roger Tredgold

Fig. 9: Dr Roger Tredgold  Fig. 10: Louise Bond-Williams

Fig. 10: Louise Bond-Williams