We use cookies

Using our site means you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies. Read about our policy and how to disable them here

Away from knights in shining armour, there’s a flourishing HEMA revival of nineteenth century and early twentieth century martial arts. These, however, are often connected to surviving, living lineage martial arts - Bartitsu was a hybrid martial art practiced in Edwardian London that combined Japanese judo/jiujitsu with French cane fighting and English wrestling and boxing, I already mentioned the earlier ancestors of modern boxing that are often called pugilism to distinguish them from current forms, while modern fencing is derived from more martial forms aimed at preparing a fencer for the duel in the Early modern era or even for fighting in war. The last of these military sword arts might be from General Patton himself, who designed a Model 1913 sabre and associated manual for the US cavalry albeit just in time to see it become completely obsolete. These surviving lineage arts can blur the lines of historic and modern martial arts - at which point are you just boxing, or wrestling, or fencing, rather than practicing HEMA?

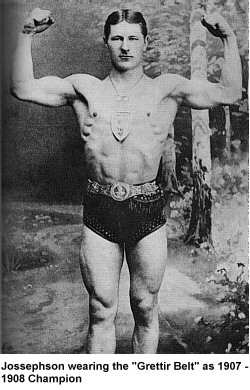

Then there are also arts which I cannot quite call HEMA because while they can show old antecedents, the system itself wasn’t recorded in detail until recently and they've maintained an unbroken lineage of teachers and fighters. In other words, they're Chidester Type Is just like boxing, but with more "fossilised" content preserving the old styles. Examples include the Portuguese stickfighting art of Jogo de Pau, and “glima”, Nordic wrestling with viking roots which boasts a continuous century of recorded championship competition in Iceland. Where these differ from other martial arts with ancient lineages is in their obscurity and their claims to represent a survival of historic arts. Many martial arts, of course, lay claim to ancient pedigree, often to the point of mythologising their origins. Yet at least in these cases there is evidence of similar practice in the past, even if the systems themselves were rarely if at all recorded.

Away from knights in shining armour, there’s a flourishing HEMA revival of nineteenth century and early twentieth century martial arts. These, however, are often connected to surviving, living lineage martial arts - Bartitsu was a hybrid martial art practiced in Edwardian London that combined Japanese judo/jiujitsu with French cane fighting and English wrestling and boxing, I already mentioned the earlier ancestors of modern boxing that are often called pugilism to distinguish them from current forms, while modern fencing is derived from more martial forms aimed at preparing a fencer for the duel in the Early modern era or even for fighting in war. The last of these military sword arts might be from General Patton himself, who designed a Model 1913 sabre and associated manual for the US cavalry albeit just in time to see it become completely obsolete. These surviving lineage arts can blur the lines of historic and modern martial arts - at which point are you just boxing, or wrestling, or fencing, rather than practicing HEMA?

Then there are also arts which I cannot quite call HEMA because while they can show old antecedents, the system itself wasn’t recorded in detail until recently and they've maintained an unbroken lineage of teachers and fighters. In other words, they're Chidester Type Is just like boxing, but with more "fossilised" content preserving the old styles. Examples include the Portuguese stickfighting art of Jogo de Pau, and “glima”, Nordic wrestling with viking roots which boasts a continuous century of recorded championship competition in Iceland. Where these differ from other martial arts with ancient lineages is in their obscurity and their claims to represent a survival of historic arts. Many martial arts, of course, lay claim to ancient pedigree, often to the point of mythologising their origins. Yet at least in these cases there is evidence of similar practice in the past, even if the systems themselves were rarely if at all recorded.

Then there are the arts with some record, but neither a surviving lineage nor evidence with detailed technical information available. Richard Marsden was determined to reconstruct Polish sabre fencing of the 17th century. The sources were scarce, but I think he did a good job. Hurstwic have done something similar for various forms of Viking combat. Keith Farrell has called such reconstructions "interpretive systems", and his AHA organisation has its own attempts to work out systems of broadsword and targe fighting. These are Chidester Type IIIs.

As well as arts that blur the line on historic, there are historical martial arts which we can’t call HEMA because they’re not from Europe. Whether we’re talking about China, New Zealand or Iran there is no shortage of extinct or endangered arts that people are working to preserve or resurrect.

There are also modern or non-European martial arts which provide valuable insights for the HEMA practitioner. The value of cross-training boxing or judo when examining Pugilism or Bartitsu should be obvious. So should the benefits of a grounding in modern fencing theory when examining historical fencing arts. Yet consider the benefits of kenjutsu (Japanese swordsmanship) to learning longsword fencing, or of training kali (Philipine arts for the knife, stick and machete) if interested in dussack fighting.

If this list of an article was to have a conclusion, it would be: do what you want, just be honest about it. There's nothing wrong with wanting to do an undocumented historical fighting style, but once you've made your aspis, dory and panoply you should be honest about exactly what sources you do or don't have for your "hoplite martial art". Do what you want to, and if there's a historical martial art that interests you, pursue it. Just don't dilute the term HEMA by applying it to some invented and unevidenced system. That said, go have fun!

Then there are the arts with some record, but neither a surviving lineage nor evidence with detailed technical information available. Richard Marsden was determined to reconstruct Polish sabre fencing of the 17th century. The sources were scarce, but I think he did a good job. Hurstwic have done something similar for various forms of Viking combat. Keith Farrell has called such reconstructions "interpretive systems", and his AHA organisation has its own attempts to work out systems of broadsword and targe fighting. These are Chidester Type IIIs.

As well as arts that blur the line on historic, there are historical martial arts which we can’t call HEMA because they’re not from Europe. Whether we’re talking about China, New Zealand or Iran there is no shortage of extinct or endangered arts that people are working to preserve or resurrect.

There are also modern or non-European martial arts which provide valuable insights for the HEMA practitioner. The value of cross-training boxing or judo when examining Pugilism or Bartitsu should be obvious. So should the benefits of a grounding in modern fencing theory when examining historical fencing arts. Yet consider the benefits of kenjutsu (Japanese swordsmanship) to learning longsword fencing, or of training kali (Philipine arts for the knife, stick and machete) if interested in dussack fighting.

If this list of an article was to have a conclusion, it would be: do what you want, just be honest about it. There's nothing wrong with wanting to do an undocumented historical fighting style, but once you've made your aspis, dory and panoply you should be honest about exactly what sources you do or don't have for your "hoplite martial art". Do what you want to, and if there's a historical martial art that interests you, pursue it. Just don't dilute the term HEMA by applying it to some invented and unevidenced system. That said, go have fun!