We use cookies

Using our site means you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies. Read about our policy and how to disable them here

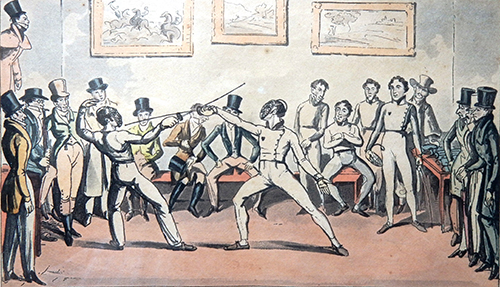

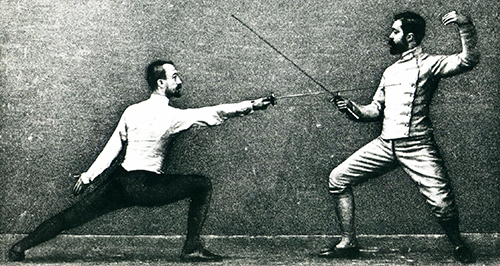

Although masks were gradually becoming accepted, the old style of fencing with the head back for protection was still taught. As a result, a fencer's whole weight rested on the back leg, making lunging and recovery slow and clumsy. If an attack was parried, the riposte was delayed until the attacker had recovered his guard. Long phrases without a hit on either side were regarded as the highest state of the art. Fencing was impressive but stereotyped. The man who perhaps more than any other changed fencing from an art form to a modern sport was Francois-Joseph Bertrand, a Parisian master who flourished in the 1830s. Known as the Napoleon of the foil, he swept away the conventions of the time, demanding above all speed and mobility. The weight of the body moved forward to rest equally on both feet. A parry was followed by an immediate riposte and fencers were free to advance or retire according to circumstances. He reduced the eight recognised parries to four – quarte, tierce (which he preferred to sixte), septime and seconde (rather than octave) – and encouraged the use of time thrusts and counter-attacks. His system was put into practice in England by his most notable pupil, Pierre Prevost, who taught at the LFC for ten years and handed over to his son, Camille Prevost, one of the great masters of the 19th century. The classical French style can be clearly recognised in Camille Prevost's illustrations to the Badminton Fencing (Fig. 2).

Although masks were gradually becoming accepted, the old style of fencing with the head back for protection was still taught. As a result, a fencer's whole weight rested on the back leg, making lunging and recovery slow and clumsy. If an attack was parried, the riposte was delayed until the attacker had recovered his guard. Long phrases without a hit on either side were regarded as the highest state of the art. Fencing was impressive but stereotyped. The man who perhaps more than any other changed fencing from an art form to a modern sport was Francois-Joseph Bertrand, a Parisian master who flourished in the 1830s. Known as the Napoleon of the foil, he swept away the conventions of the time, demanding above all speed and mobility. The weight of the body moved forward to rest equally on both feet. A parry was followed by an immediate riposte and fencers were free to advance or retire according to circumstances. He reduced the eight recognised parries to four – quarte, tierce (which he preferred to sixte), septime and seconde (rather than octave) – and encouraged the use of time thrusts and counter-attacks. His system was put into practice in England by his most notable pupil, Pierre Prevost, who taught at the LFC for ten years and handed over to his son, Camille Prevost, one of the great masters of the 19th century. The classical French style can be clearly recognised in Camille Prevost's illustrations to the Badminton Fencing (Fig. 2).

Another master who did much to popularise fencing in England was Baptiste Bertrand (no relation to F-J). He opened a salle d’armes in 1856 and founded a dynasty of fencing masters that continued with his son Felix and grandson Leon. Baptiste Bertrand was instrumental in encouraging women to fence. Following his success in teaching the three daughters of the Prince of Wales, fencing for women started to become popular. He was also called upon to stage all the fight scenes for the theatre and a number of his actor pupils became so enthusiastic that, in 1900, they formed the Foil Club.

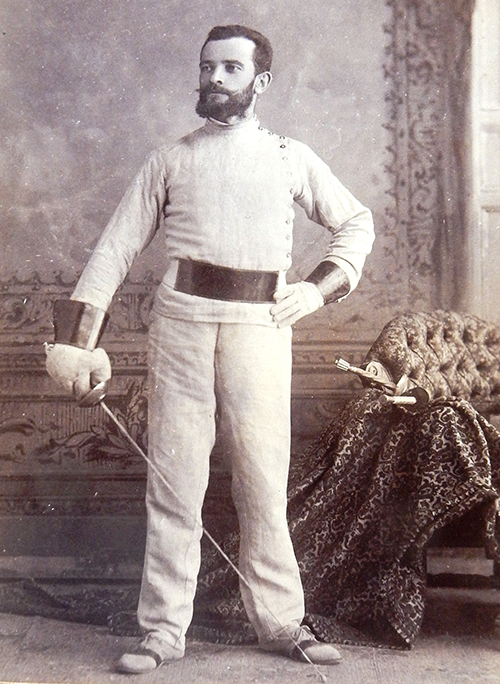

In the early 19th century fencing clothing followed the tightly cut Regency fashion supplemented by a heavily padded glove, a small wire mask covering the face only and an open-toed sandal for the front foot with a leather projection which made a resonant sound when slapped on the floor. The foil itself was supplied with a French or Italian handle and had a blade only about 80 cm long with a solid round or open figure-of-eight guard of steel or brass, a cord-bound square handle and around or urn-shaped pommel. By the 1850s the mask had become more substantial, the jacket and trousers more practical and the foil blade had increased in length to 87 cm, with a standard open figure-of-eight guard bent upwards and a heavy oblong pommel, as shown in an early photograph of a fencer (Fig. 3).

Another master who did much to popularise fencing in England was Baptiste Bertrand (no relation to F-J). He opened a salle d’armes in 1856 and founded a dynasty of fencing masters that continued with his son Felix and grandson Leon. Baptiste Bertrand was instrumental in encouraging women to fence. Following his success in teaching the three daughters of the Prince of Wales, fencing for women started to become popular. He was also called upon to stage all the fight scenes for the theatre and a number of his actor pupils became so enthusiastic that, in 1900, they formed the Foil Club.

In the early 19th century fencing clothing followed the tightly cut Regency fashion supplemented by a heavily padded glove, a small wire mask covering the face only and an open-toed sandal for the front foot with a leather projection which made a resonant sound when slapped on the floor. The foil itself was supplied with a French or Italian handle and had a blade only about 80 cm long with a solid round or open figure-of-eight guard of steel or brass, a cord-bound square handle and around or urn-shaped pommel. By the 1850s the mask had become more substantial, the jacket and trousers more practical and the foil blade had increased in length to 87 cm, with a standard open figure-of-eight guard bent upwards and a heavy oblong pommel, as shown in an early photograph of a fencer (Fig. 3).

The latter half of the century saw the introduction of knee breeches (Fig. 2), although many fencers continued to wear long flannels, such as the LFC master Vital Lebailly (Fig. 4).

The latter half of the century saw the introduction of knee breeches (Fig. 2), although many fencers continued to wear long flannels, such as the LFC master Vital Lebailly (Fig. 4).

The epee was adopted in France in the second half of the 19th century as a result of the dissatisfaction felt by amateurs with the conventions of the foil. By the turn of the century, it had spread to England as had the light Italian fencing sabre. Individual foil competitions began to take place during the last two decades and in 1901 the Amateur Fencing Association was formed.

The epee was adopted in France in the second half of the 19th century as a result of the dissatisfaction felt by amateurs with the conventions of the foil. By the turn of the century, it had spread to England as had the light Italian fencing sabre. Individual foil competitions began to take place during the last two decades and in 1901 the Amateur Fencing Association was formed.